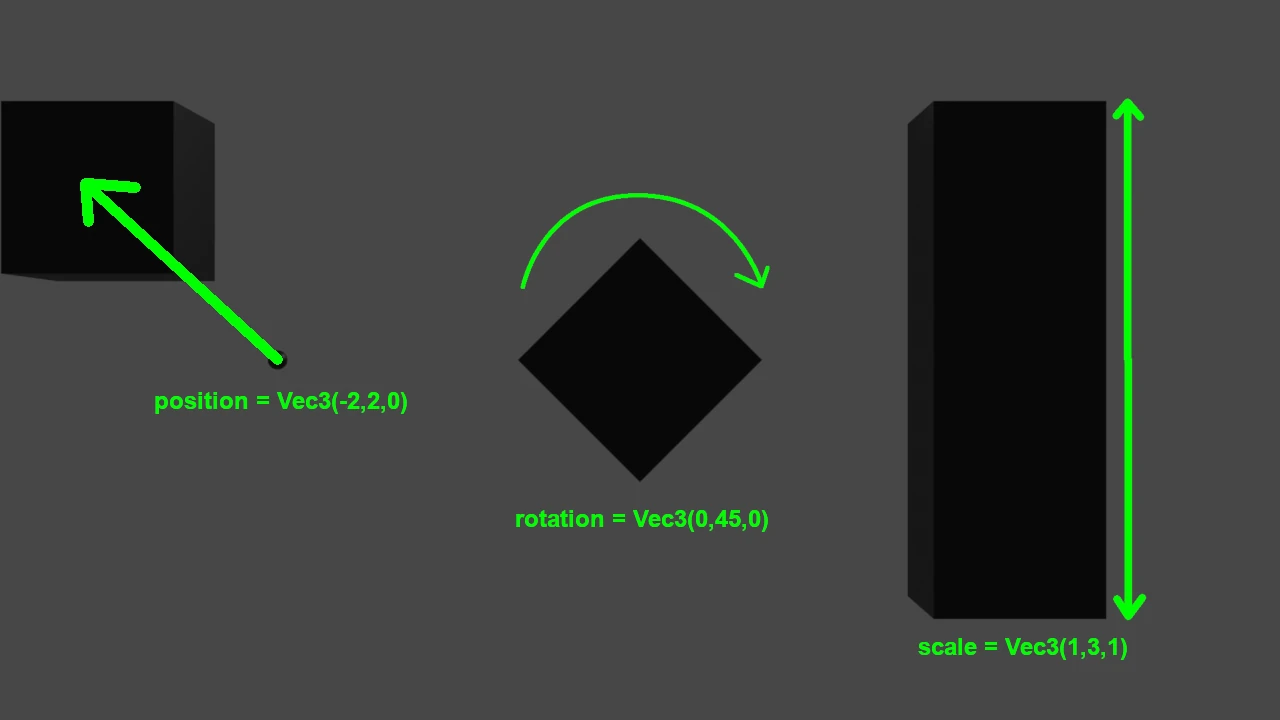

Vectors are an integral part of any game engine and are used in many of its aspects. They are necessary to represent the position, rotation and scale of objects, physical interactions like contacts and collisions, and in some instances to depict matrices rows or columns (depending on who you are talking to).

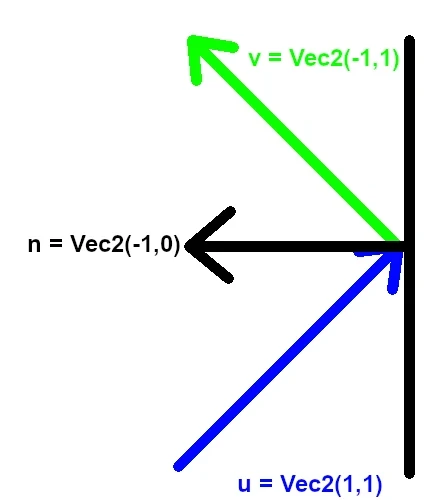

Matrices are very often used to calculate the rotation of objects and the camera, or even to represent the position, rotation and scale of an object instead of using three different variables for them. Reflections are essential for any physics engine, since they are used to determine the direction of the bounce when two objects collide between each others.

It is needless to say that since this component is so often used in any game engine, it needs to be as fast as possible in order to squeeze every bit of performance out of the engine.

During my second year of study, my classmates and I have all been tasked to take part in the creation of a game engine, with our teacher as the lead of the project. Once every two weeks we were given a new task and every week we would discuss each student’s advancement and our teacher would give pointers on how to improve our current code.

I have been given multiple tasks over the course of this project, but I think the most interesting one was when I worked with vectors, which is what I’m going to present in this post.

I needed to create a class for each of the 3 dimensions used in game engines, being Vec2, Vec3 and Vec4.

Here is an example of the 3D vector implementation:

template<typename T>

class Vec3

{

public:

union

{

struct

{

T x;

T y;

T z;

};

T coord[3];

};

const static Vec3 zero;

const static Vec3 one;

const static Vec3 up;

const static Vec3 down;

const static Vec3 left;

const static Vec3 right;

const static Vec3 forward;

const static Vec3 back;

As you can see, the implementation is pretty simple: a struct that contains the vector coordinates and an array to, for example, iterate through the vector coordinates. All of this in a template class, to be able to handle multiple types. There are also some static variables to make some usual vectors readily accessible.

After that, most of the work was to create the multiple mathematical methods that would be used in the engine, for example:

static T Dot(const Vec3<T> v1, const Vec3<T> v2)

{

return v1.x * v2.x + v1.y * v2.y + v1.z * v2.z;

}

static Vec3<T> Cross(const Vec3<T> v1, const Vec3<T> v2)

{

return Vec3<T>(v1.y * v2.z - v1.z * v2.y,

v1.z * v2.x - v1.x * v2.z,

v1.x * v2.y - v1.y * v2.x);

}

template<typename ReturnT = float>

ReturnT Magnitude() const

{

return std::sqrt(SquareMagnitude());

}

static Vec3<T> Lerp(const Vec3<T>& v1, const Vec3<T>& v2, T t)

{

return v1 + (v2 - v1) * t;

}

And that is basically it, vectors are not that complicated after all (it would that much more painful to make a physics engine otherwise). However, I kept thinking “That’s it?” after finishing all this, there had to be some sort of optimization to apply here.

When I presented my work on the first week, apart from other minor mishaps on my part, my code did not really have any major optimization flaw (there are not many ways to implement vectors ultimately). My teacher did, however, turned my attention to one flaw with how vectors are implemented.

Vectors have one small flaw in every implementation: a singular vector coordinates are aligned, but when operations with multiple vectors are at play, the values are not aligned in the fastest way possible.

For example, if we look at how the vectors are stored in memory:

As you can see, the x, y and z coordinates of the two vectors are not aligned together.

The goal would be to obtain this:

Coordinates are correctly aligned together.

After some more pointers given by my teacher, it became clear what more I could do: using Structure of Arrays (SoA) and Array of Structures of Array (AoSoA) instead of Array of Structures (AoS).

SoA is way of organizing the data in a struct, as an alternative to AoS which could be described as the “default” approach. As an example:

struct Vec3AoS {

float x;

float y;

float z;

}

// Here, each struct has a single variable for each coordinate.

// If you need multiple vectors, you would need to create an array containing the struct

// (ex: std::array<Vec3AoS, 8> vectors)

template<int N>

struct Vec3SoA {

std::array<float, N> xs;

std::array<float, N> ys;

std::array<float, N> zs;

}

// Here, the struct is used to represent N number of vectors, their coordinates stored in xs, ys and zs.

// If you need multiple vectors, you would need to instantiate this struct with N as the number of vectors you need.

// (ex: Vec3AoS<8> vectors)

On top of those two option, there also exists a third type that is more of an hybrid of the two: AoSoA.

struct Vec3AoSoA {

std::array<float, 8> xs;

std::array<float, 8> ys;

std::array<float, 8> zs;

}

// Here, the struct is used to represent exactly 8 vectors, their coordinates stored in xs, ys and zs.

// You can't use more than 8 vectors, and using less means wasting memory space.

// (ex: Vec3AoSoA vectors)

An advantage of AoSoA is, since the size of the array is fixed, we can use SIMD expressions which can only take arrays with a size in a power of 2. SIMD expressions are instructions that allows us to process multiple elements “at the same time”, which, of course, can drastically reduce the time a function takes to execute.

It’s also important to note that none of these are necessarily “better” than the other. It depends on the context. Here, since all of the vector variables will often be accessed at the same time, using SoA and AoSoA is the better option.

The goal was to be able to align multiple vectors coordinates in order to use intrinsics commands on those. From that, came the NVec classes:

template<typename T, int N>

class alignas(N * sizeof(T)) NVec3

{

public:

std::array<T, N> xs;

std::array<T, N> ys;

std::array<T, N> zs;

This class stores each vector coordinates in a separate array that is aligned on the size of the type (T) times the number of vectors given (N). It organizes values using SoA, which aligns the values just like we want. However, on top of that I also created two aliases:

using FourVec3f = NVec3<float, 4>;

using EightVec3f = NVec3<float, 8>;

//This transforms the SoA class into an AoSoA one, which will allow us to use SIMD expressions and optimize it even further!

And now that we have our values aligned and AoSoA aliases set up, it is time for some intrinsics!

Intrinsics are a set of methods (different depending on your processor manufacturer) whose implementations are handled by your compiler. These intrinsics methods allows us to use SIMD expressions.

Having an Intel CPU, I needed to use Intel’s intrinsics methods which are organized in different sets depending on the processor generation. For FourVecfs, I used the SSE set for x86 architectures since it handles xmm registers which have sizes of 128 bits (or 16 bytes) at most, which is exactly the size of xs, ys and zs. EightVecfs, as for it, uses AVX2 instructions, which are only available for post-Haswell CPUs. AVX2 uses the ymm registers which have sizes of 256 bits (or 32 bytes).

In the current implementations, each function has an intrinsic and non-intrinsic version. For example, for the dot product:

static std::array<T, N> Dot(NVec3<T, N> v1, NVec3<T, N> v2)

{

std::array<T, N> result;

for (int i = 0; i < N; i++)

{

result[i] = v1.xs[i] * v2.xs[i] +

v1.ys[i] * v2.ys[i] +

v1.zs[i] * v2.zs[i];

}

return result;

}

template <>

inline std::array<float, 4> FourVec3f::DotIntrinsics(FourVec3f v1, FourVec3f v2)

{

alignas(4 * sizeof(float))

std::array<float, 4> result;

auto x1 = _mm_load_ps(v1.xs.data()); //Loads xs into a xmm register

auto y1 = _mm_load_ps(v1.ys.data()); //Loads ys into a xmm register

auto z1 = _mm_load_ps(v1.zs.data()); //Loads zs into a xmm register

auto x2 = _mm_load_ps(v2.xs.data()); //Loads xs into a xmm register

auto y2 = _mm_load_ps(v2.ys.data()); //Loads ys into a xmm register

auto z2 = _mm_load_ps(v2.zs.data()); //Loads zs into a xmm register

x1 = _mm_mul_ps(x1, x2); //Multiplies all the values of v1.xs by those of v2.xs and stores them back into x1 since we don't need it's value anymore.

y1 = _mm_mul_ps(y1, y2); //Multiplies all the values of v1.ys by those of v2.ys and stores them back into y1 since we don't need it's value anymore.

z1 = _mm_mul_ps(z1, z2); //Multiplies all the values of v1.zs by those of v2.zs and stores them back into z1 since we don't need it's value anymore.

x1 = _mm_add_ps(x1, y1); //Adds all the values of x1 with those of y1 and stores them back into x1 since we don't need it's value anymore.

x1 = _mm_add_ps(x1, z1); //Adds all the values of x1 with those of z1 and stores them back into x1 since we don't need it's value anymore.

_mm_store_ps(result.data(), x1); //Stores the result into the "result" array, so that we can return and use the values of x1.

return result;

}

The first method is pretty straightforward: we make a for loop to calculate the dot between each element of v1 and v2.

For the intrinsic method, we start by creating an array to store our result in and align it on the correct amount of bytes, because otherwise it might crash on some compilers. We then load the coordinates using _mm_load_ps. Next, we store the results of _mm_mul_ps and _mm_add_ps directly in the first argument because we won’t be needing the value for later. Finally, x1 is stored into the result array with _mm_store_ps which is then returned by the method.

Funnily enough, I initially encountered errors when doing the same methods for EightVecs, when tge only thing I needed to change was the _mm prefix (the prefix for SSE instructions) by _mm256 (the prefix for AVX2 instructions)… simple as that.

For every size that is not 4 or 8, the regular dot should be called, otherwise it will throw an error.

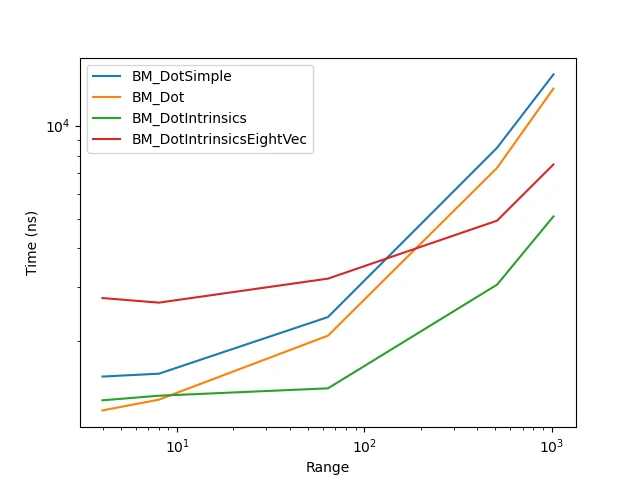

Here’s a graph of the benchmark of my Dot methods done on Windows 10, with an Intel i7-4790K@4.00GHZ CPU, compiled with MSVC v16.4.

BM_DotSimple: a benchmark of iterating through two arrays of vectors to calculate the dot product between each pair.

std::array<Vec3f, 8> array1;

std::array<Vec3f, 8> array2;

for (size_t j = 0; j < 8; ++j)

{

Vec3f::Dot(array1[j], array2[j]);

}

BM_Dot: a benchmark of the non intrinsics version of Dot for FourVec3f shown earlier.

BM_DotIntrinsics: a benchmark of the intrinsics version of Dot for FourVec3f shown earlier.

BM_DotIntrinsicsEightVec: a benchmark of the the intrinsics version of Dot for EightVec3f.

As we can see, the time taken by the NVec Dot methods is less than for the Simple version; the intrinsics version is, however, only faster than the Simple one for the intrinsic FourVec version and when handling a very large amount of vectors for intrinsic EightVec. Let’s see how much time we save on a more complex methods like Reflect() (for vector reflections):

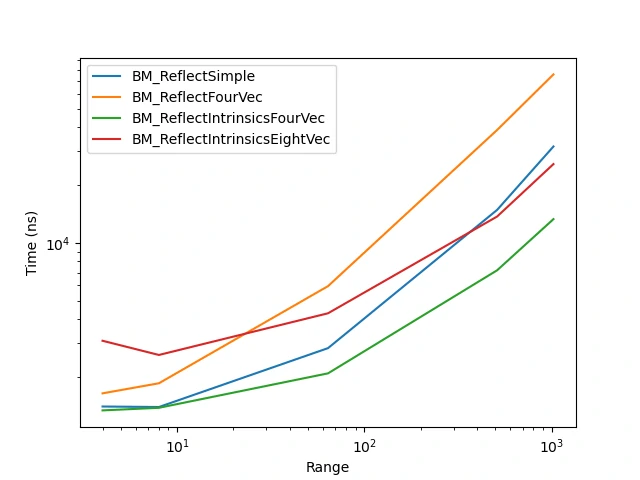

We can see a similar trend on this methods, however the ReflectFourVec is this time much slower and using intrinsic EightVec is only slightly faster for very large amount of data.

This significant difference between EightVec and FourVec is likely due the cacheline. A FourVec3f has a size of 48 bytes which fits within the cacheline (64 bytes) whereas a EightVec3f (96 bytes) doesn’t, hence why it’s so much slower.

I think I learned a lot on how data is handled on the hardware part and how to optimize my data so that the CPU can exert its full power. I got to be more familiar with the concept of AoS, SoA and AoSoA as well as the use of intrinsics commands to handle big chunks of data.

Overall, it made me more sensitive to how I code things.